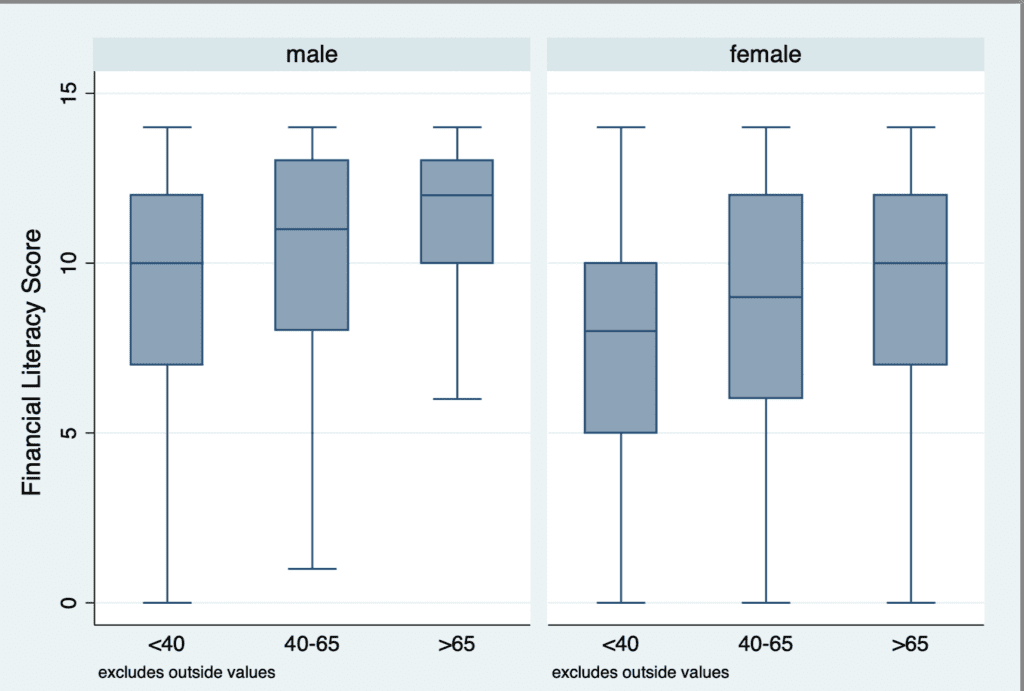

An analysis by our colleagues at USC Center for Economic and Social Research finds a persistent gender gap in financial literacy, with women performing worse than men between the ages of 40 and 65. This suggests that value of tailoring programs to the needs of older women may be significant.

In any country around the world, individuals’ ability to effectively manage their finances and plan for the long-term is critical to financial well-being in old age. Research shows that by both subjective and objective measures, consumers globally lack the financial knowledge and skills to confidently secure their own future. At the same time, demographic change is occurring faster than financial, health and social systems can be expected to adapt – as life expectancies increase, family structures contract, and individuals are left to face increasingly complex social protection systems and financial marketplaces. As a result, older adults today are facing longer periods in retirement, with dwindling formal and informal economic support.

Yet, research also shows that older women may experience greater economic vulnerability in than older men. In the United States, as in much of the world, gaps in financial security exist for older women, and widowed and never-married women, women with disabilities, and minority women have particularly high rates of economic insecurity in older age.

Existing evidence suggests that differences in individual financial literacy as well as confidence and self-efficacy play a role in the gender gap in financial security in the U.S. Recent analysis conducted by a team at the Center for Economic and Social Research examined the existing gender gaps in financial literacy present in the US population.[1] Using data from the nationally representative Understanding America Study (UAS), the study assessed the extent to which the gender gap in financial literacy exists in women and men in the crucial years before retirement, ages 40-65, and its implications.

Researchers found that using validated measures of financial literacy (the widely-used battery of financial literacy questions developed by Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchell) and cognitive ability (a standard cognitive reflection test) women and men in this age group had similar levels of cognitive ability but that women performed significantly worse on measures of financial literacy, as well as a range of measures of self-reported life satisfaction related to health and well-being. This gender gap in financial literacy persists, despite adding further statistical controls for background characteristics including education, employment, marital status, and race.

Our further analysis shows that financial literacy has significant positive associations with life satisfaction, income, health and activities of daily living. While this is true for both women and men, controlling for financial literacy generally increases the negative gender gap on indicators related to health and well-being. The positive effect of increased financial literacy on life satisfaction and well-being is larger for men than for women.

What are the implications of these findings? Our results suggest that financial literacy matters for all, but financial literacy alone cannot explain the differences in well-being for men and women. However, for older women, this relationship is more complex: an increase in financial knowledge does not raise well-being as much as it does for men. This potentially points to the larger role of structural or environmental issues for women.

Growing evidence shows that interventions that deliver financial education can affect financial knowledge, as well as positively affect behavior. However, reviews of financial education in the U.S. and around the world have also shown that surprisingly, few programs target older women specifically, with the emphasis either on younger women or older adults more generally. Our findings suggest that tailoring programs to the needs of older women may be significant and that there may be value in approaches specifically targeted at older women that emphasize how to translate knowledge into actions and, ultimately, well-being.

This research is supported by a grant from Evidence for Action, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

This blog was originally published on the University of Southern California’s website.